Tuning in to critical research:

Tuning in to critical research:

Making It In America: Revitalizing Manufacturing In The USA

Research From the McKinsey Organization

There is a lively debate about the “tax burden” on U.S. companies and possible relief coming in the drafting of the “tax reform” legislation in the House and Senate, and the eagerness of the White House to get the varying tax bills hammered into legislation for the President’s signature.

This was an important theme for then — Candidate Donald Trump in the 2016 campaign — the promise “bringing jobs back” to the Heartland, among other regions. (Remember the Carrier Air Conditioning dust-up…with Indiana plant jobs going to Mexico?)

Will American companies repatriate their offshore financial holdings if a lower tax rate and other accommodations become the Law-of-the-Land?

Will American companies use the money to create many new jobs? Or might the funds be used in some other way — including share re-purchases and sending dividend checks to investors?

The corporate sector could be in the middle of a contentious public debate about the role of company and society — is there a real obligation to create domestic jobs?

Is there a need for more jobs in U.S.-based manufacturing, which at least in the political rhetoric of the day is among the hardest hit by foreign competition, outsourcing, et al?

Corporate managers could find themselves in the middle of this debate depending on the course of public policy in the months ahead.

If tax reform legislation becomes law, what will U.S.-based companies do in terms of creating more jobs? In your town? Will your company be focused on by stakeholders expecting new jobs to be created?

Where did the American manufacturing jobs go?

We tuned in to a new report generated by McKinsey & Company and the McKinsey Global Institute; the work of the professionals resulted in comprehensive research and solid advice for American manufacturing firms (and stakeholders).

Top Takeaways From the Report:

The erosion of U.S. manufacturing is not a foregone conclusion. In the decade ahead, three factors will give the U.S. manufacturing sector a chance to turn around — (1) increased market demand, worldwide (2) application of new technologies and (3) for companies, value chain optimization.

It will take a concerted effort on the part of both private and public sectors and various stakeholders to make the revitalization successful over the coming decades. Jobs can be created — but they will likely be a different kind and fewer in number as automation continues to replace humans.

From G&A Institute – Some Background:

The Industrial Revolution changed the fundamental nature of work in the United States all through the 20th Century.

At the start of the 1900s, more than half of the population worked on farms. At the end of the century, only about 3% of the workforce was working in agriculture. The dramatic shift was from farm-to-factory.

Manufacturing accounted for about 12 million jobs in the United States in 1950 (at mid-century); increased to the peak of almost 20 million jobs by 1980; the total is at about 12.5 million in 2017.

Consider that the U.S. population was 150 million in 1950; 226 million in 1980; and is 325 million today. Manufacturing jobs in America steadily declined as the national population increased.

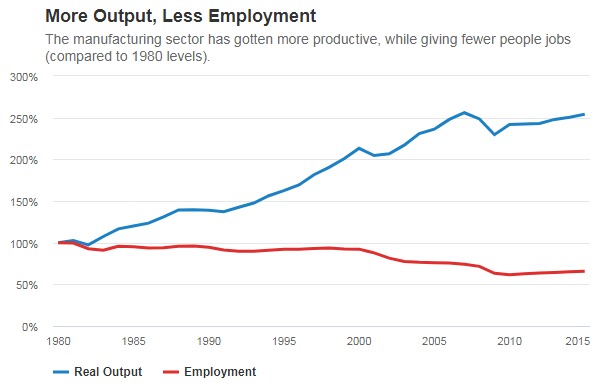

While manufacturing employment has steadily declined, the production/value added has steadily increased.

Therein lie the challenges for many Americans who have been displaced, and for public policymakers who try to figure out the way forward in an era of fewer workers/more output.

Since the mid-1970s, U.S. manufacturing jobs have steadily declined. The bright spots today, say McKinsey researchers, are in pharmaceuticals, electronics, and aerospace.

Most other sectors are in steady decline in terms of manufacturing value-added, with many small- and mid-size firms especially hard hit. That has a ripple effect on the economy; for example, thriving large-caps are left without a broad and deep domestic supply chain for collaboration.

Keep in mind, too, that economists generally project that for each manufacturing job, there are four other jobs created (in the supply chain, for retailers. bankers, service providers, trades workers, etc).

So – can we turn things around?

The McKinsey Global Institute finds that the United States could boost annual manufacturing value-added by more than US$500 billion (that’s 20% over current value-add) by the year 2025. That will require what some folks in other countries call “Industrial Policy,” something the U.S. policymakers have avoided since the vigorous debate about “IP” in the early-1980s.

What Is Needed? Here Are Highlights From the McKinsey Professionals:

While manufacturing has been buffeted by waves of change, the United States remains one of the most lucrative markets on the globe.

Demand here for heavy machinery, equipment, and building materials could increase if public sector investment revives from a 50-year slump. That takes political will (and courage) to make happen.

Demand is soaring in emerging economies, with more than one billion (“b!”) global urban residents earning enough to create what McKinsey estimates to be market demand of $30 billion for consumer goods (especially in the markets of Africa, Brazil, China and India).

Great complexity will present challenges for corporate managers; think about the dizzying change possible in auto buying, apparel, luxury goods…with different price points, ethnic/language/cultural tastes, life cycles, and more.

The U.S. Manufacturing Sector will have to seriously consider and then meet these challenges worldwide from the American base.

McKinsey sees the evolving American manufacturing landscape as “Industry 4.0,” with multiple technology advances converging.

Like the emergence and growth of data analytics, machine learning, machine-to-machine learning, human-machine interaction, augmented reality systems, digital communication, automated plants, and ability to turn out volumes in goods or highly-customized products, as needed.

And think of the global reach and influence of The Internet of Things!

Where is your company’s value chain in all of this?

McKinsey researchers say this is why companies must change their business models, footprint and sourcing policies, and practices. (An example offered is John Deere adding sensors to its farm equipment to guide farmers on their land. Another is an aerospace firm providing leasing services including the availability of pilots and “power-by-the-hour”.)

One trend to watch is U.S. firms bringing manufacturing back to this country. It is happening in refined petroleum products, petrochemicals, and fertilizers (domestic fracking is a factor, with domestic raw inputs more cost-effective).

“Total factor performance” is a buzzword catching on, says McKinsey: “footprint decisions” for a U.S. manufacturer include logistics, lead time, productivity, proximity to suppliers, transport costs, and risk (think of various types of risks posed in some distant countries in the supply chain).

In the Report, McKinsey sets out details of three scenarios for increasing export growth, the share of domestic content in finished goods, higher technology adoption and growth of consumption for manufacturers to consider. These are presented with industry-by-industry analysis.

# # #

Added Context from the G&A Institute Team:

Consider the reality of 1980 to 2016 Job Losses in Manufacturing in the USA

MIT Technology Review in November 2016 published a piece by Mark Muro: “Manufacturing Jobs Aren’t Coming Back.”

Reason: the decades-long decline of U.S. manufacturing employee and the highly-automated nature of the sector’s recent revitalization should be high on the list of “why” — for example, automation has eliminated literally millions of American jobs.

The collapse of labor-intensive commodity manufacturing and expansion of advanced manufacturing left many millions of workers feeling abandoned, irrelevant and angry. They became the forgotten middle-class workers no longer in the factory. We saw the results in the November 2016 election.

Notes Muro, who is Director of Policy at the Brookings Institution: The trend lines of production data since 1980 show the liquidation of more than one-third of U.S. manufacturing jobs — from 18.9 million jobs down to 12.2 million by 2016. Most of the jobs were lost in the American Midwest (the so-called “Rust Belt”).

MIT researchers David Autor and colleagues demonstrated that this was in large part due to lower-cost imports from China.

One of the leverage points that President Donald Trump is apparently attempting to use to “bring back jobs” as promised in the campaign is the rejection of the Trans-Pacific Trade Partnership Agreement, the threat of putting tariffs on China-made goods and re-negotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (governing US-Mexico-Canada trade).

As we prepared this report the Trump Administration launched an investigation into China “dumping” in the aluminum industry. This is one of the most dramatic moves of the last two decades. The U.S. Department of Commerce worked with the Aluminum Association to develop the case for the investigations. The U.S. International Trade Commission would make a final decision as to what action to take — perhaps two years off from now.

Here’s the key point for stakeholders to keep in mind: While we have less manufacturing employment in the USA,

we have more real manufacturing output!

Adjusted for inflation, the American manufacturing sector is turning out more value than it has ever been (this is up 250% since 1980).

Robots, machine learning, machine-to-machine communication, artificial intelligence — all are increasingly important factors in keeping the United States strong in manufacturing.

“Job intensity” is the loser. “People” are losing if they worked in manufacturing jobs that were affected. This is a dramatic example of what has been happening:

Here’s the equation that underlies the reality: Creating US$1 million in production value took 25 jobs in 1980 and takes only 5 people today! We are not “de-industrializing” the American manufacturing sector; we are “depopulating” the employment in the sector.

# # #

For Managers to Consider:

As the McKinsey Report tells us, revitalizing the entire U.S. manufacturing sector will require a dramatic scale-up of “what works,” and the task is bigger than any single entity can manage.

Manufacturing will need support from the public sector and assurance of both long-term policies and funding. EVERYONE has to be at the table.

The value-add of U.S. manufacturing is steadily “up” (that’s very encouraging!) while the employment rate is “steadily down” (so discouraging for so many of us). Therein are many challenges for the corporate and public sectors!

The focus on many large-cap companies on STEM education initiatives in their corporate responsibility / corporate citizenship initiatives and programs is a solid contribution to the way forward for the American society. Long-term, there will be many beneficiaries as a result of this focus.

A variety of corporate support for STEM education, employee training and re-training and continuous training will make a real difference over time (STEM: science, technology, electronics, math.). The corporate sector’s contributions will help to create millions of new types of jobs for American youth as they mature and begin careers.

In our analysis of U.S. corporate sustainability / responsibility / citizenship reporting, we see a good number of STEM initiatives by companies of varying sizes, and in an expanding universe of industries and sectors.

G&A’S Recommended Next Steps:

- Consider conducting a supply chain analysis of your business models, footprint and sourcing policies, and practices (such as offshoring, onshoring, moving work from employee base to subcontractors).

- Factor the total cost of your value chain including logistics, lead time, productivity, proximity to suppliers, transport costs, and a variety of risks. (Think especially about various dimension of corporate ESG risk, and various types of risks posed in some distant countries in the supply chain that could affect reputation and valuation, and freedom to operate).

- Map Risk and Opportunities for your organization across your entire value chain (where, for example, are investors focusing in the value chain?).

# # #

References for You:

- The full report is at: https://www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/americas/making-it-in-america-revitalizing-us-manufacturing

- Note that the download to the Technical Appendix is available with link in the Report.

- McKinsey & Company Report authors are: Dree Ramaswamy, Partner, McKinsey Global Institute in Washington, D.C.; James Manyika, Chairman of the Institute, based in San Francisco; Gary Pinkus, McKinsey Senior Partner in San Francisco; Katy George, Senior Partner McKinsey in New Jersey; Jonathan Law, Partner, New York Office; Tony Gambell, Partner, Chicago Office. and Andrea Serafino is a Consultant.

The very informative MIT Technology Review essay is at: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/602869/manufacturing-jobs-arent-coming-back

The very informative MIT Technology Review essay is at: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/602869/manufacturing-jobs-arent-coming-back- A reliable source of information about U.S. employment is the U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics platform: https://www.bls.gov/

- There is demographic information about the United States of America that might be of interest at:

http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/us-population/

Created November 20, 2017

If you are interesting in learning more about the work of Governance & Accountability Institute and its portfolio of resources, tools and service offerings, please click here